As I embark on my fourth year having students complete a six-week Civics Action Project, it has become one of my favorite units. The authentic, real-world connections students make, the ownership they take in choosing and leading their projects, and the pride they feel during the showcase make this unit incredibly powerful. I’ve seen students who were previously disengaged suddenly light up with passion when given the chance to support something meaningful to them. It’s the kind of transformation that reminds me why I became a teacher.

Why a Civics Action Project is Critical Now More Than Ever

At the start of the unit, I do a four-corners activity with the students. One of the questions I pose to them is, “My voice can make a difference.” Year after year, almost every student walks to the “Disagree” or “Strongly Disagree” corner of the room. I hear students say things like, “I don’t think my voice matters,” or “I’m only a teenager.” This project proves to them that they can make a difference. In today’s world, where democracy faces increasing challenges and misinformation spreads easily, it is more important than ever to equip students with the skills to engage in civic life. Many young people feel disconnected from government and policy making, but a Civics Action Project changes that by showing them how they can be active participants in their communities.

Beyond understanding how government works, a project like this fosters essential skills like critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaboration, skills that are not only crucial for democracy but also highly sought after in today’s workforce. It provides students with opportunities to develop these abilities in a meaningful context, helping them become informed and engaged citizens who are prepared for the future.

The Power of Project-Based Learning for Civics

Project Based Learning (PBL) is all about engaging students in real-world challenges, and a Civics Action Project embodies this approach perfectly. The Gold Standard PBL framework highlights key elements that make a project successful: a challenging problem or question, sustained inquiry, authenticity, student voice and choice, reflection, critique and revision, and a public product.

National Geographic Civics and Citizenship resource is designed with these principles in mind, incorporating inquiry-based activities and project-based learning strategies that help students connect civics concepts to real-world issues. All National Geographic Learning resources emphasize student-driven exploration, making them a strong foundation for meaningful civic engagement.

Stage 1: Examining Self and Civic Identity

Every great PBL experience starts with an engaging question or challenge. In the Civics Action Project, students begin by brainstorming issues they encounter in their own lives and conducting surveys to identify community concerns. This process helps them connect their personal experiences to broader civic issues, ensuring authenticity and relevance in their learning.

Stage 2: Identifying an Issue

Inquiry is a key component of PBL. In this stage, students research potential topics, explore data, and identify organizations or individuals working on similar issues. The sustained inquiry process mirrors PBL best practices by encouraging students to analyze problems deeply before jumping to solutions.

Stage 3: Researching and Investigating

PBL emphasizes real-world connections, and the Civics Action Project does this by having students engage with experts, conduct interviews, and examine systemic influences on their chosen issue. This step fosters critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaboration, essential skills for any civic leader. I love seeing students get excited when they hear directly from local officials or community leaders because it makes their work feel more significant.

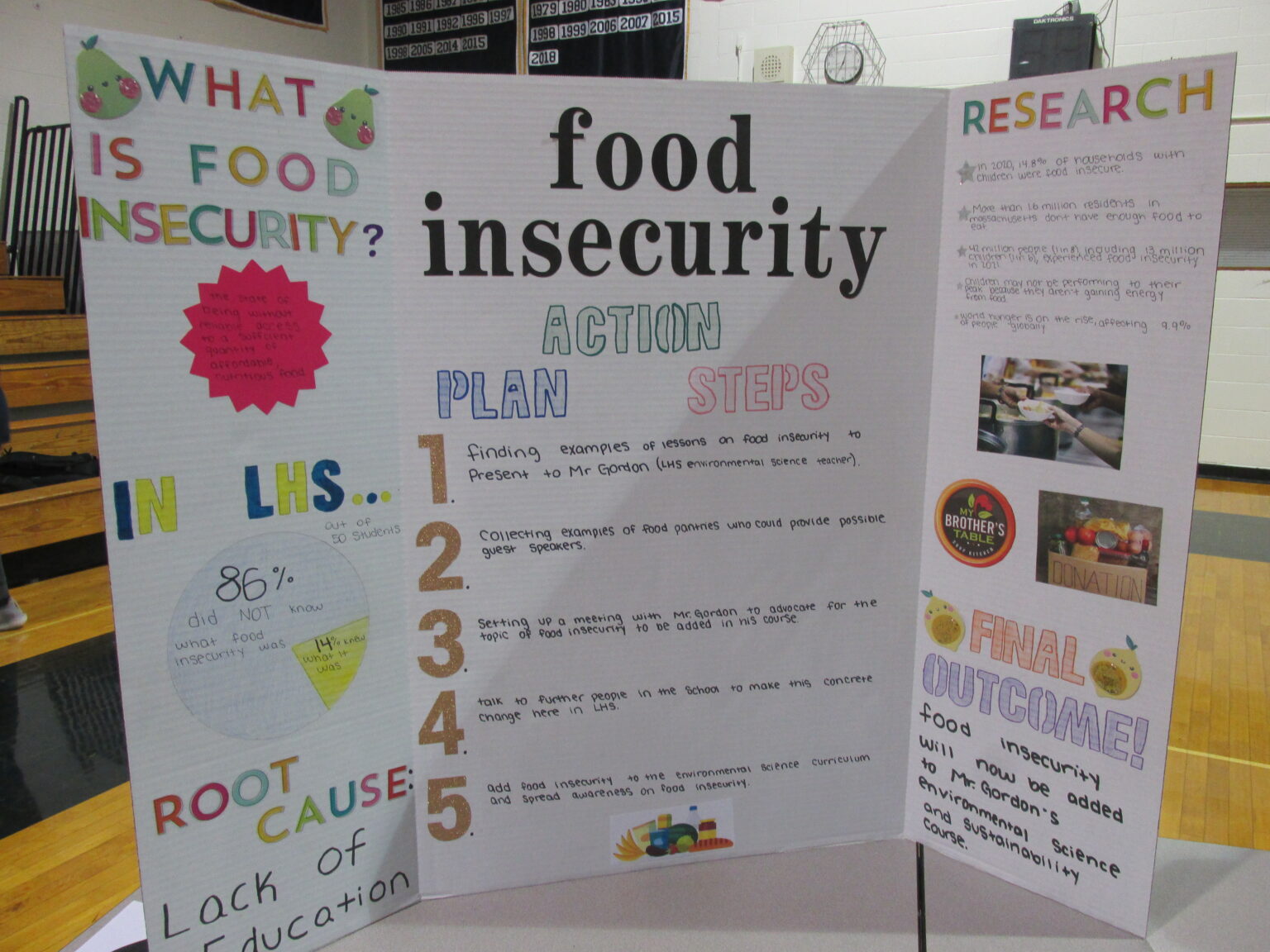

Stage 4: Developing an Action Plan

Voice and choice are central to PBL. Students take ownership of their learning by designing their action plans. They identify key decision-makers, develop persuasive arguments, and map out strategic steps for civic engagement. This phase is where creativity and negotiation come into play, aligning with the skills identified as most valuable in today’s workforce.

Stage 5: Taking Action

Whether presenting at a school board meeting, launching a campaign, or collaborating with a nonprofit, students experience the impact of their work beyond the classroom. Seeing students take real steps to influence their communities is one of the most rewarding parts of this process. I’ve had students continue their projects well after the six weeks are over, and some have even met with lawmakers and gotten them to sign bills. That’s when I know this unit has truly made a lasting impact.

Stage 6: Reflecting and Showcasing

Reflection and public presentation are crucial in both PBL and the Civics Action Project. One of my favorite moments every year is watching students proudly share their work at the showcase. The confidence they gain from seeing their efforts recognized is incredible. The showcase also reinforces the idea that their voices matter and that young people have the power to make change. Seeing their faces light up as they present is a moment I look forward to every year.

Setting Up for Success Using PBL Frameworks

To ensure a Civics Action Project is successful, teachers should apply best practices from Project Based Learning:

• Clearly define the driving question: Ensure students understand the central problem they are addressing.

• Foster sustained inquiry: Encourage research, discussion, and expert engagement.

• Provide student voice and choice: Allow students to select topics and design their action plans.

• Support critique and revision: Create opportunities for feedback and improvement.

• Emphasize public presentation: Have students showcase their work to authentic audiences.

Conclusion

The Civics Action Project is more than just a classroom assignment. It is an immersive, practical learning experience grounded in PBL principles. At a time when democratic engagement is more critical than ever, this project helps students see their role in shaping their communities and making a difference. Seeing students light up as they tackle real-world issues, find their voices, and take pride in their work makes this one of the most rewarding units I teach. If we want our students to leave our classrooms ready to tackle society’s challenges, we must provide them with opportunities that mirror those challenges. With the right structures in place, students won’t just learn about democracy, they’ll practice it. And for me, that’s the most rewarding part of all.

More About the Author

David Forster is a veteran high school educator in Massachusetts with a passion for hands-on, project-based learning. He has taught a variety of Social Studies courses and recently expanded into EdTech marketing, where he helps connect educators with innovative learning tools. Through his work in product marketing, he has created teacher-focused content and resources to support meaningful classroom engagement.

References

Civics Project Guidebook, www.doe.mass.edu/rlo/instruction/civics-project-guidebook/index.html#/. Accessed 28 Jan. 2025.

“Gold Standard PBL: Essential Project Design Elements.” PBLWorks, www.pblworks.org/what-is-pbl/gold-standard-project-design. Accessed 30 Jan. 2025.